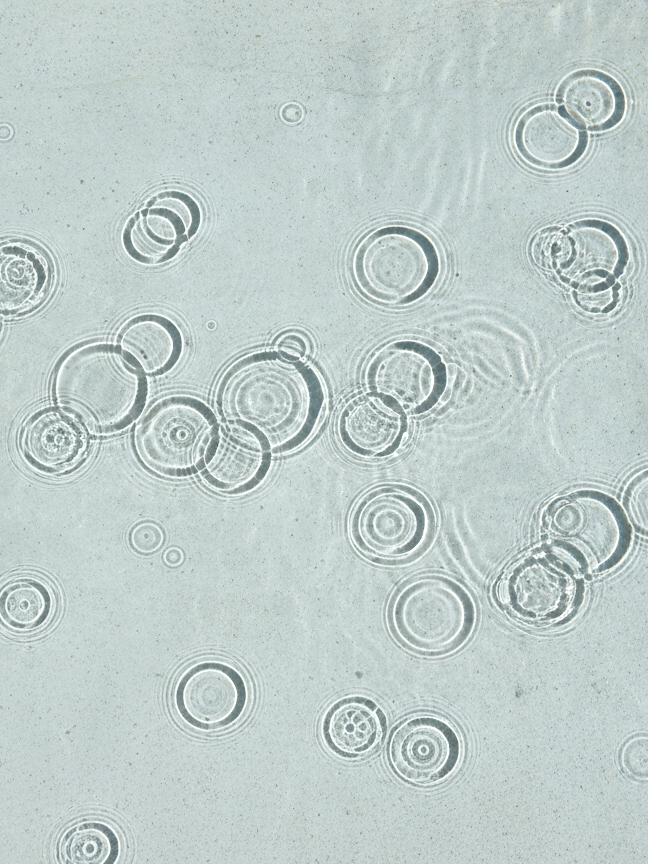

ripples

swim the pool

deeper

the words,

read as breath,

widening on ripples,

then silent

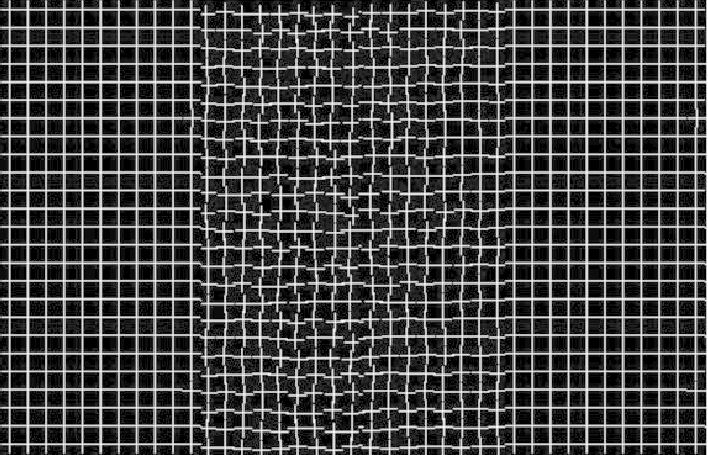

healing grid illusion

conceived by ryota kanai,

cognitive neuroscientist, utrecht university

the healing grid illusion.

at the core, lies a grid of perfect symmetry. it’s the edges that fray into deliberate irregularity—crooked crosses, broken lines. so, when one fixes their gaze upon the circular focal point in the center, something transformative begins.

the brain, ever-craving harmony, aligns itself with the clarity presented at the center, invoking a process known as perceptual fading. it fills things in. the periphery becomes a canvas for the brain’s reconstructive artistry.

the central circle plays an essential role. it corrals visual attention. when you lock attention within a circumscribed space, the brain starts filling in the peripheral with what it “knows” ought to be there. such “guesstimates” signal stability.

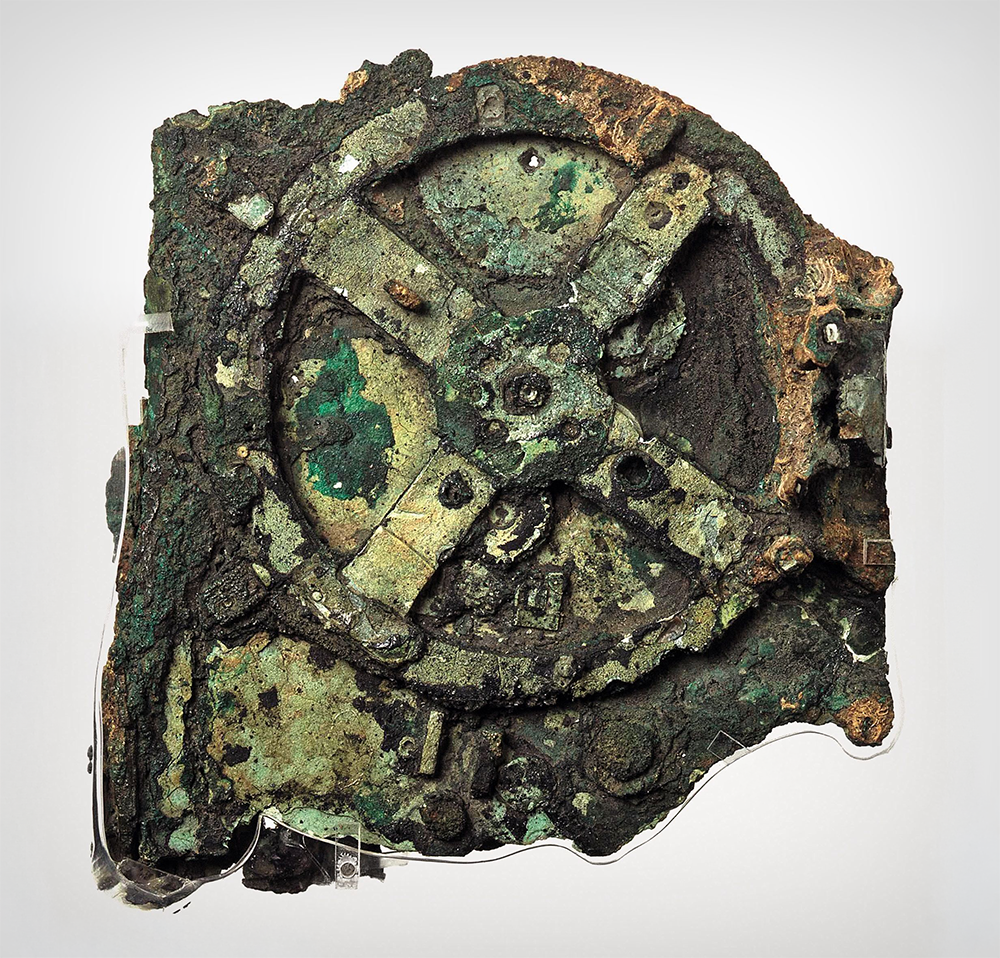

Antikythera mechanism

this mechanism, discovered in a shipwreck off the greek island of antikythera in 1901, is a masterpiece of ancient ingenuity. dated to around 100 bce, this bronze device is the oldest known analog computer, designed to calculate astronomical positions and eclipse cycles. it contains at least 30 intricate gears arranged in concentric circles, each tooth perfectly meshed to turn in harmony. without each gear turning precisely, the mechanism’s ability to track the complex motions of celestial bodies—sun, moon, and planets—would collapse into chaos. each cog’s rotation was a note in a celestial symphony that rivals today’s technology.

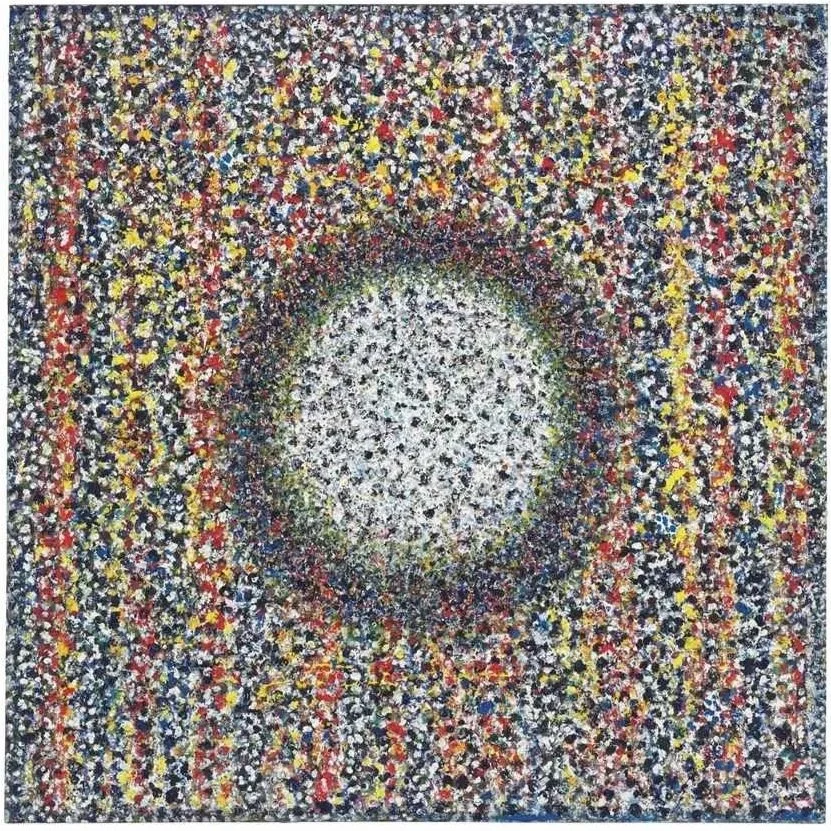

richard poussette-dart

Artist Richard Pousette-Dart did not see the circle merely as a shape. For him, it was a primal symbol charged with existential power.

His paintings of abstract circles constitute one of the most profound visual meditations on eternity and spirituality in 20th-century art.

Pousette-Dart’s pointillist work for hospitals “Presence Healing Circles,”envision a different kind of recovery. This artist was deeply spiritual. He placed his works in sterile white corridors to radically reform clinical space. His circles test the healing ability not only of art, but of the form. They serve as experiments in empathy.

round and round

round and

round and

round again

i have no beginning

i have no end

“i’m a circle” by jack hartmann

the brain, in its uncanny machinery, responds to simple shapes profoundly. one compelling study that mapped neurons revealed an almost primordial serenade evoked by visualizing circles. these shapes — smooth, endless, unyielding in their repetition — guide our minds into a state of “affective ease.” an unwilled surrender to calm.

when your psyche processes the jagged edges of triangles, your psyche strains. a visceral response is provoked. but, a circle promises your brain a respite. it demands less laborious contemplation, less cognitive wrestle. in the labyrinth of neural circuits, we find the circle not just a shape, but a refuge.

Circular rainbows

30,000 ft above. “If you glance out the windows on the right side of the plane, you might catch sight of a circular rainbow suspended in the clouds. That ring of light reveals the true shape of a phenomenon we think we know so well.”

These circular rainbows form when sunlight passes through countless tiny raindrops. The light bends as it enters, reflects off the droplet’s inner surface, and then bends again as it exits. Each hue unfurls into the spectral display that we call a rainbow.

So why do we usually see only an arc from the ground? The Earth blocks the lower half, leaving us that familiar curve. But from a plane or a mountain top, the full circle appears—because you can see the entire cone of refracted light. Without the Earth in the way, every rainbow would blaze as a brilliant, spinning halo in the sky.

Peripheral Drift Illusion

This illusion, often utilizing circular arrangements, causes parts of the image to appear to move or swirl, especially when viewed out of the corner of the eye. It is strongest in circular designs and results from how the brain processes differences in light intensity, motion, and depth. Eye movement and blinking intensify the illusion, producing the sensation of shifting or rotating rings.

“Mom, it tastes better in a circle.”

Studies demonstrate that people tend to associate round shapes—such as plates, glasses, and food forms—with positive taste experiences. For example, beer drunk from curved-sided glasses is rated fruitier and more intense, and round plates enhance the perception of sweetness in dishes like cheesecake.

This roundness effect extends beyond just food shapes to packaging and menus, where rounded elements are linked to sweeter taste associations.

In essence, the circle shape influences the sensory perception of taste, making food and drink seem more flavorful and enjoyable compared to angular or square shapes.

The technique of centered circles, where components are stacked or placed revolving around the plate’s center, often elevates the dish’s stature and focus. Others adopt off-center circular designs to create dynamic tension and visual interest. This approach is seen as both a classic and modern plating style among Michelin-star chefs and fine dining experts.

Cutting and serving food in circular forms or arranging elements in circles signifies a deliberate artistic choice to enhance sensory perceptions including taste, as circles are associated with sweetness and completeness in culinary psychology. This preference especially influences your enjoyment of “hedonic foods,” those foods consumed mostly for pleasure.

This shape-sweetness association is partly cultural, because today we associate circles with pies and cakes. But, this preference is also rooted in evolutionary psychology — because round foods like fruits and berries register as safe and nourishing.

So, your giant rainbow lollipop being round is not just random design, but a choice meant to draw in your brain and taste buds.

paleolithic artistry

france. archeologists discover intricately engraved (often ivory) disks, that date to the ice age. these “rondelles” bear the marks of sophisticated paleolithic artistry. carved with spellbinding precision, they date back 11,000 to 18,000 years.

each rondelle, barely larger than a coin, is etched with detailed wildlife—a leaping deer, a swirling mammoth trunk—that capture prehistoric life in frozen motion. when spun, these delicate carvings mysteriously came alive. a primitive zoetrope, they melded art, life, and myth with magic.

deep with symbolic meaning, these mesmerizing artifacts, allow us to glimpse the dawn of humans fascination with illusion and storytelling—a journey that would eventually lead to the grandeur of the cinema. these discs capture one of humanity’s earliest dances of symbolic expression, under a paleolithic moon.

the wheels of the bus…

social circles

“The next best thing to being wise oneself is to live in a circle of those who are.” — C. S. Lewis

george washington preferred circular or oval rooms for his presidential levees—formal social gatherings where he stood at the center and greeted guests, with everyone on equal standing and equidistant from him. he ordered curved walls be added to his philadelphia residence.

architect james hoban, influenced by washington, introduced an “elliptic saloon” into the design of the white house, deemed the blue room. its shape became a model for the oval office, which even today symbolizes continuity, openness, and equality in presidential receptions.

a perfect circle

“A circle is a round straight line with a hole in the middle.” — Mark Twain

In the cold glow of MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory in 1963, twenty-something Ivan Sutherland sat with the room-sized TX-2 computer. He had an idea. Others didn’t think so. Drawing on a digital screen? Impossible.

Indeed Sutherland, armed with a light pen, was about to create the first time pixels came together to form a circle.

And it conjured a magical revolution. Sketchpad, a digital canvas where lines bent to human will, circles traced themselves with effortless grace, and shapes obeyed commands like living objects. This was new.

Sketchpad’s brilliance shone not just in interactivity, but in its visionary soul—introducing ideas decades ahead of their time. Now, objects carried relationships and rules, allowing a line to stubbornly stay parallel or a circle to remain perfectly round, no matter how they were stretched or moved.

Under the guidance of luminaries like Claude Shannon and Marvin Minsky, Sutherland’s thesis sparked entire fields: computer-aided design, 3D modeling, and virtual reality. Sketchpad was a bold, raw feast served when computers barely went beyond counting—and it still flavors every digital interaction today, born from the mind of a visionary who dared to redraw possibility’s limits.

Negative Entropy

The opposite of entropy is known as negentropy, also negative entropy, or syntropy. While entropy refers to the measure of disorder, randomness, or energy loss within a system (tending towards chaos and increasing over time according to the second law of thermodynamics), negentropy represents order, organization, and structure—essentially things becoming more organized and functional.

Negentropy is a temporary condition in which systems become more highly ordered than their surroundings. Examples of negentropy include life processes that convert less ordered materials into more ordered biological structures and social systems that organize chaos into useful order. Negentropy is often described as the force or characteristic of attraction, counterbalancing entropy’s characteristic of repulsion

“Our task must be to free ourselves… by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature and its beauty.”

— Albert Einstein

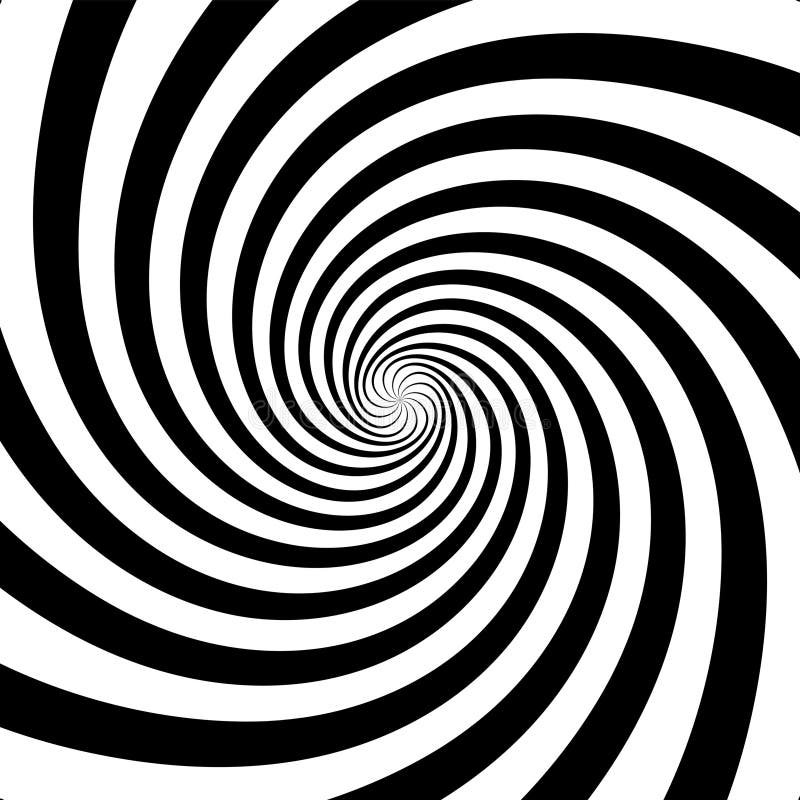

hypnotic spiral

A rotating spiral or pattern of concentric circles can create the sensation of movement or depth. The hypnotic effect works because of geometric tricks—often, the circles or dots within move linearly, but synchronized motion tricks the mind into seeing them as spinning or rolling around the center. This induces a sensation of movement and sometimes even trance-like states, as the visual system attempts to follow the repetitive, swirling shape.

Halo, anish kapoor

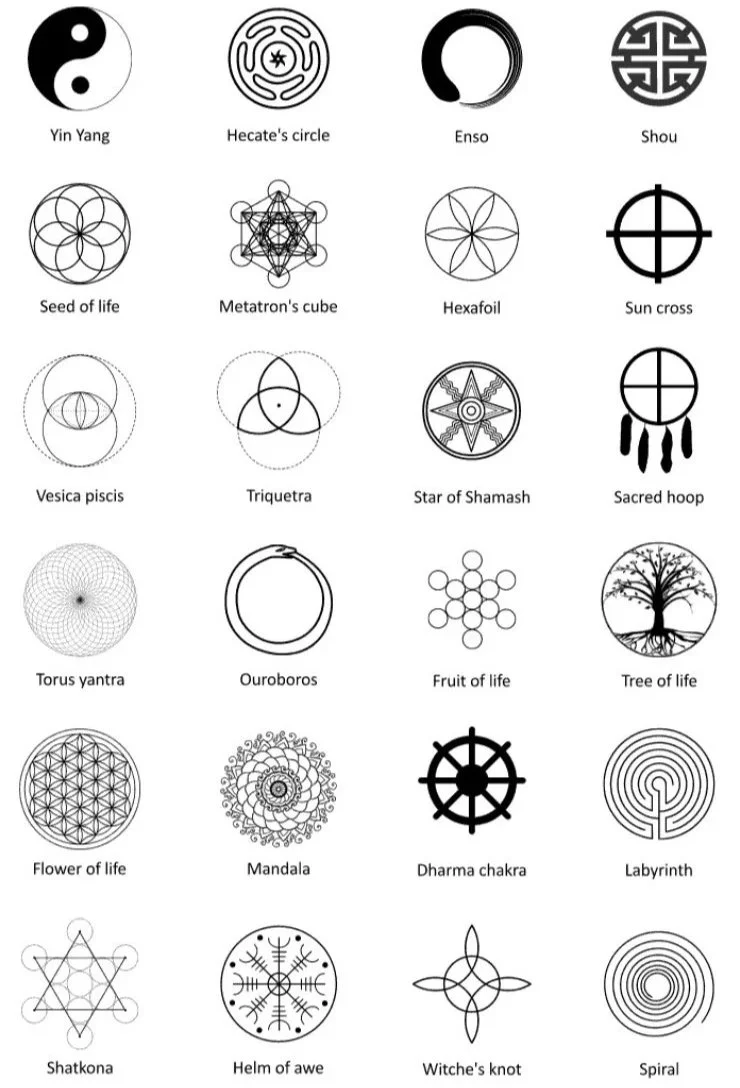

28 ancient circular symbols

circular definition

When you see a circle from just a few scattered points, your brain is performing a remarkable trick of science.

First, your visual system, starting with the primary visual cortex, detects those points as signals. Then, higher brain areas like the fusiform gyrus assemble those dots into a familiar shape: a circle.

This is a prime example of what psychologists call “Gestalt principles,” specifically the principle of “closure.” Your brain has this incredible tendency to “fill in the gaps,” turning incomplete snapshots into whole, meaningful forms.

Neuroscientific studies also point to “illusory contour” neurons in the primary visual cortex that respond when a shape like a circle is implied. These neurons help complete visual patterns by linking sparse points into perceived continuous forms via recurrent feedback between higher and lower visual brain areas.

It’s all part of the same survival trick that saved our ancestors — spot a face in the crowd, a shape in the shadows, and know instantly whether it’s friend, food, or threat. Still…

Chris wood

“I like to draw circles, because you never have to worry about the corners.” — Demetri Martin